As long-time readers of this blog know I have lived slightly over ten years in Finland, basically one third of my life and almost my whole adulthood. A couple of months after my son was born I applied for citizenship, and it was granted slightly over a week ago (even if I didn’t find out until last Friday). It mirrors that well-trodden path elsewhere from immigrant to citizen, with the addition that it’s obviously the first time I go through it and it’s also a relatively novel phenomenon for the country I can now call my own.

The applicable Finnish law has significantly changed during my time here. Until 2007 time as a student or worker without A status (whose granting was always a mystery to me) didn’t count towards citizenship, which meant the 6 years I had spent in Finland by then were useless. This changed when four years ago the law was modified so that all the time spent in the country legally counts toward citizenship, regardless of whether it was spent as a student, a worker, a Finn’s family member or another reason. The residency requirement was 6 uninterrupted years for singles, 4 for those married to a Finnish citizen with the last 2 being continuous (i.e. if you moved away and came back even if you had lived here long enough you had to wait another two years to apply).

Besides the residency requirement, the law also stated that applicants should have a good command of one of the official languages of Finnish and Swedish (e.g. proven with the official Yleiskielentutkinto test which I took in 2007) plus a clean criminal record. Even minor fines could count against you. You also needed to show a demonstrable source of income.

I had no problem with those prerequisites, but the challenging bit for me was that when filling out the citizenship form I had to list all my absences from Finland since I moved here. Especially after ten years working in a multinational corporation and constant trips to visit my parents it was a challenging exercise (as you can probably gather from this Flickr collection). I created an Excel table with Destination(s), Travel purpose, Dates & Duration that gave me a total of over 90 absences from Finland (it could have been worse, but I was a full time student for the first 3 years). I understand very well why this is required (visiting e.g. Helmand in Afghanistan wouldn’t look good, I guess unless you’re a peacekeeper) but it was a chore. Thankfully I had my old passports, Dopplr & Flickr to help me out. I’m positive the list submitted was accurate. Based on the processing times published in the Immigration Service’s website I expected it to take at least a year, if not more.

Funnily enough I was awarded Finnish nationality right before the law was loosened up a little again (now you need one or two years less of residence, but you still have to prove the other points).

Unlike say, Spain, the United States, or Mexico, Finland doesn’t organize a ceremony of any kind for awarding citizenship nor an oath of allegiance of any sort. You “just” get a letter (blame it on Finnish distaste for useless ceremony if you will). As of last Tuesday, I’m now a Finn (or at least a Finnish citizen).

Every one of us is a product of our background and our experiences. Since the turn of the century I’ve learned to understand the Finns: their language and the way it modifies their thought processes, their love of nature, their diligence for hard study and hard work but respect of free time, their love of exercise and sports, their complex relationship with coffee and alcohol, their modesty, openness, directness and practicality, their trust in their state institutions (especially for education and security), their love of salmiakku, rhubarb pies, mämmi, new potatoes with dill, salmon, reindeer, sausages, more berries than I can name in languages other than Finnish and Karelian pies, their view that having sauna next to a lake or sea is the best way to end a summer’s day, the impressive mood changes matching with the seasons, their love of hockey and victories over Sweden, their stubbornness to the point of suicide (a.k.a. sisu, they say), and many other things. During my time here I’ve taken the tasks of internalising the positives, tolerating the negatives and trying to bring a bit of my own to the table. It’s not about this place and this people aren’t good. It’s about we can be better (crap, it still feels weird to say we).

If I didn’t like it here warts and all I wouldn’t have stayed this long. During that process of contact and adaptation, you start identifying yourself with your host society if the relationship with it is at the very least cordial. I won’t lie if I say I applied for citizenship almost purely for practical reasons: I have now the right to live permanently with my wife and son; travel to certain places like the US, Africa and the Middle East is easier (Finns have visa-free travel to 170+ countries, Mexicans to 120+) while coming back should be easier; I now have the right to influence where my taxes are used and where the society is going through my vote; I can even move freely to another EU country if I have a reason to do so.

However, I find myself in the situation where my sense of identity is being modified. Regardless of whether I liked it or not, one of the many factors that defined me in the eyes of others was the fact that I’m a Mexican in Finland, a foreigner, an immigrant. That meant (depending on the audience) that I always had to be extra careful and try to give the best possible impression, as they wouldn’t necessarily see me, but what I represent. It is a huge responsibility to feel you’re the only sample somebody knows of a country of 110 million people or of the 200,000 immigrants in Finland and you have the chance to make or break their stereotypes. While that is still somewhat relevant the turn from outsider to insider makes it weaker. I have proven myself. I’ve been measured, examined and approved. I am a part of this society and nobody can take that away from me. I am still me, but what me is evolves with my experience. Whichever term you want to use: new Finn, naturalized Finn, Mexican-Finn, Finn-Mexican, Finn of Mexican origin, etc. it is not anymore foreigner or immigrant.

Since this whole phenomenon is so new for Finland itself I know I will again be doing some trailblazing (sometimes I feel like Antonio Banderas in 13th Warrior, while on others like an Old West pioneer) and I know people with sympathies with the extreme right will never see somebody like me as equal to them. The good news is that my vote counts too and we are equal before the law. If they can’t live with that it’s their problem, not mine.

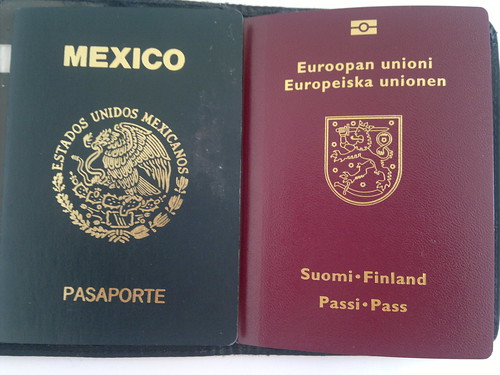

I am currently traveling for the first time abroad using a Finnish passport besides my Mexican one. It feels nice to be part of the society I’ve spent so long trying to fit with without losing the official link to my roots in the place where I was born.

Kiitos.

Great post. It truly conveys your feelings. Congratulations on the new era of your life as a Finnish-Mexican!

Felicidades! Yo también, desde abril, ya soy ciudadana belga (tras 4 años de vivir aquí), aunque por lo que escribes, es mucho más fácil adquirir la nacionalidad en Bélgica (no nos hacen examen de idioma, ni checaron mi récord criminal -aunque ése si lo checaron cuando solicité la visa- y tampoco me preguntaron cuántas veces he dejado el país). Yo también solicité la nacionalidad por las razones que mencionas.

Estoy completamente de acuerdo contigo: no se trata de ver quién es mejor o qué lugar es mejor, sino aceptar que todos somos diferentes y que esas diferencias son lo que hacen que las culturas sean diferentes y por qué no, encantadoras. En lo único que no concuerdo contigo es que aún con la nacionalidad, todavía me siento como un “alien”, es una cuestión personal, y tiene mucho que ver con la reacción visceral que a veces tengo al enfrentarme con situaciones que aún no tienen sentido para mí. Es probable que mi punto de vista cambie en el futuro, cuando tenga unos cuantos años más de expeciencia viviendo aquí.

Oye, me puedes explicar la extraña relación que tienen los escandinavos con el alcohol? Desde mi punto de vista (y de acuerdo con mi experiencia en Suecia), casi no toman alcohol, pero cuando lo hacen es “a morir”, pues es muy caro. No te parece una relación un poco enfermiza? Me parece menos saludable tomar mucho de un jalón que una chela/vaso de vino un poco más seguido.

PS no te olvides de usar tu pasaporte mexicano cuando vayas a México 😉

Sobre las reacciones viscerales te entiendo, yo también las tenía. Es parte del proceso de adaptación cultural: mientras la situación sea inesperada y choque demasiado con tus expectativas las tendrás.

Los nórdicos ven al alcohol como “fruta prohibida” y “pasaporte a la libertad”, de ahí que lo tomen como sprint en lugar de maratón. Estoy de acuerdo que no es la manera más saludable del mundo y no comparto la práctica, pero así son.

PD Sí, lo sé. Normalmente viajo con los dos.